|

|

| IMPROVE YOUR ENGLISH TUTORING SERVICES | October 2012 Newsletter |

In this issue:

|

| IYE STUDENT NEWS |

Student Achievements

Congratulations to Lynn Chui, who scored a 36 on her ACT English Test. It really doesn’t get any better than that. Way to get a perfect score, Lynn!

Congratulations also go to Irene Hsu, a senior at Lynbrook High School. Her short story was one of the first-place winners in the 81st Annual Writer’s Digest Writing Competition, which is open to writers of all ages. Her story will be published in an upcoming issue of the magazine.

Our Recent Bookworms

It takes persistence to finish something you start, even an exciting book!

Last month, Ria Vidyasagar finished reading The Little Princess, which contains unique 304 unique vocabulary words!

Alex Yang and Eugene Choi have both finished reading Tom Sawyer, which has 38 chapters with 472 vocabulary words.

Angela Chen has completed the novel The Secret Garden, which is 27 chapters long with 237 unique vocabulary words.

Eric Zhang recently completed Mark Twain’s The Man Who Corrupted Hadleyburg, which contains 275 vocabulary words.

David Schwartzman finished A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which contains 1,243 vocabulary words!

Manny Luu finished 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which contains 1,404 vocabulary words!

Annie Pham has finished Call of the Wild, which contains 472 vocabulary words.

Rachel Zhang finished reading Pride and Prejudice. That’s 61 chapters with 1,029 vocabulary words!

Diagramming Book

Yunji Lee completed the first half of the diagramming book last month! And a hearty congratulations to Catherine Kim, who has completed the whole thing!

Diagramming Challenge Winner

Sara Zhang correctly solved last month’s diagramming challenge! The sentence was, “The most important questions you’ll learn to ask at Deep Springs, or indeed at any college, are simple but not easy,” which he diagrammed as:

For winning, Sara will receive a $10 gift certificate to Barnes & Noble. Congratulations!

Student Writing of the Month

Applying Strunk and White’s Rule 16: Use Definite, Specific, Concrete Language isn’t easy, especially when you’re describing something abstract.

Many creative writers, such as poets and novelists, favor the use of metaphor when they want to describe an abstraction in concrete details. A good metaphor can highlight apt similarities between two disparate things, actions, or ideas.

A metaphor won’t work in every essay, but it is certainly a useful tool to practice using.

For her essay on dreams, eighth grader Rachel Zhang got rid of a prosaic description by using an extended metaphor that carries on a lengthy comparison between the act of trying to recall a dream and fishing. The result? A colorful introduction that avoids sending the reader off to daydreams of his own!

Back to top | More Newsletters | Back to Improve Your English

| COLLEGE FOCUS |

UC San Diego

An Ivy League Education in the California Sun

Called one of the “Public Ivies,” the University of California, San Diego is not only among the best national public universities, but it is arguably better than most private schools, including the “Ivies” themselves. Washington Monthly, for example, ranks it higher than Harvard or Berkeley in its national university list. While you should view all university rankings with the deepest skepticism, this one is an eye-opener.

For one thing, its faculty, researchers, and alumni have won twenty Nobel Prizes. For another, even in these troubled times for California’s state-funded universities, UCSD spent $943 million on research and development last year—that is more than Stanford spent.

At UCSD, you’ll unravel the mysteries of the human body at the School of Medicine, work on NASA-funded nanoengineering projects at the Jacobs School of Engineering, or decipher behavioral decision making through courses in the highly ranked Department of Psychology. This college provides plenty of opportunities for hands-on, experiential learning.

Founded in 1960, UCSD occupies 2,100 acres of land along the California coast. Currently, more than 29,000 undergraduates attend classes on the campus, studying over 130 majors in its six undergraduate colleges. Each college offers its students specialized subjects along with a close-knit community. By enrolling in one of the undergraduate colleges, UCSD undergraduates enjoy the vast resources of a large public university while reaping the social benefits of a small liberal arts college.

UCSD scholars have consistently earned top academic honors, including twenty Nobel Prizes, eight National Medals of Science, and eight MacArthur Awards. More than 100 have belonged to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Alumni have won Pulitzer prizes, started multimillion-dollar companies, served in top-ranking offices in government and pursued successful careers in Hollywood. In Silicon Valley, Bill Atkinson (BA, ’74) and Guy Tribble (BA, ’75) helped develop the first Apple Macintosh. Also of local interest, the International Conference on Computer Design named a UCSD paper, “Power-Sensitive Multithreaded Architecture,” one of the five most influential papers in the conference’s thirty-year history.

UCSD is also an excellent choice for students in the humanities. You can study literary greats such as Homer, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Beckett, and Joyce. Or choose an interdisciplinary major that includes study of the Roman Empire, the Middle Ages, and the Enlightenment.

Brian E. Crie, a UCSD math tutor, says of his general education experience, “I’ve taken a couple of writing classes, a history class, and then this last year I’ve taken three Chinese classes. I’d never learned Chinese before coming to UC San Diego, and I love it here.”

Like most top-ranked schools, UC San Diego values strong English writing skills. To satisfy the university’s writing requirements, students must score a 680 or above on the SAT writing section or complete basic writing classes before passing the university’s writing exam.

Crie, a member of Tau Beta Pi, a national engineering honor society, praises an argumentation and persuasive writing class that teaches the use of quotations to support your argument—an essential in all college classes as well as at Improve Your English.

Study hard, learn to write, and choose your college well. You might be lucky enough to earn a bargain-priced Ivy League education at UC San Diego, on the sunniest part of the California coast.

Back to top | More Newsletters | Back to Improve Your English

|

|

|

Readability

by Steve High Shorter sentences are better. That’s the best-kept secret in English class. The trick is, you have to learn to write long ones first before you can edit them down. But are shorter sentences really better? Ask Kevin McGrath. Here’s what he wrote in the American Editor: Remember: Not all sentences should be short. But most of them should be. All it takes is a commitment to put the readers’ needs first, and the willingness to take a couple of minutes, even on deadline, to make it happen. McGrath is a city editor for a metropolitan daily newspaper. But what about writing for formal publication? It’s hard to think of anything more formal than legal writing, so look at this paragraph by Bryan Garner, who was an editor of the Texas Law Review (University of Texas) before clerking for a federal judge. Today, Garner is editor of Black’s Law Dictionary. Sound formal enough for you? Here’s a typical paragraph from one of his articles: Perhaps we can all agree that beginning a sentence with “but” isn’t wrong, slipshod, loose, or the like. But is it less formal? I don’t think so. In fact, the question doesn’t even reside on the plane of formality. The question I’d pose is, What is the best word to do the job? William Zinsser says, quite rightly, that “but” is the best word to introduce a contrast. I invariably change “however,” when positioned at the beginning of a sentence, to “but.” Professional editors such as John Trimble regularly do the same thing.

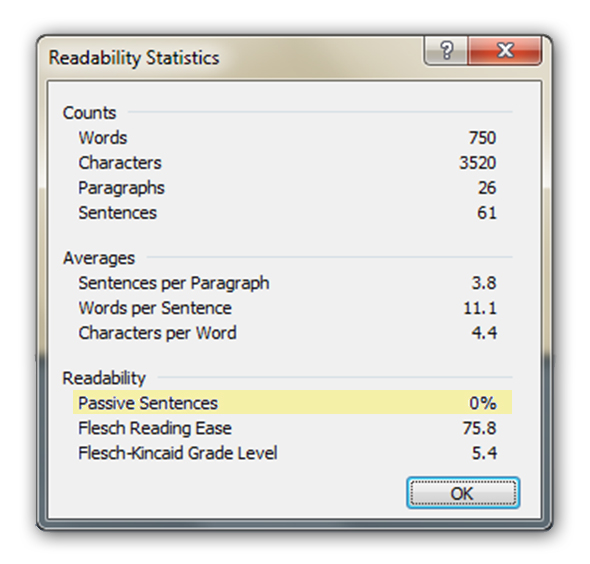

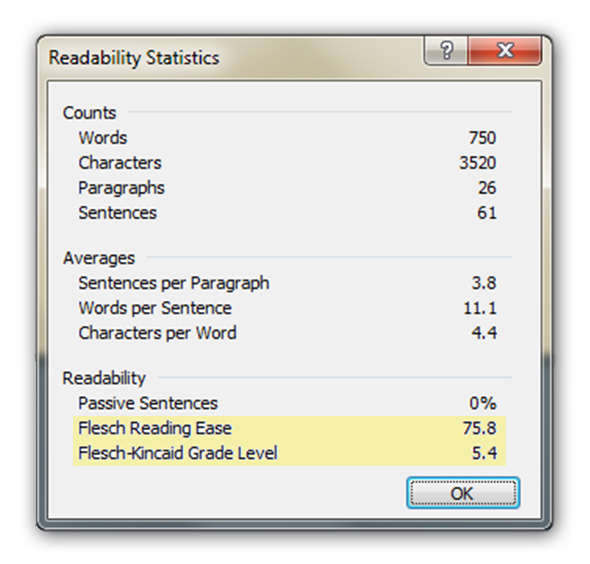

The Flesch scale, which is included in the readability statistics provided for every Word document you write, is the subject of criticism for an academic readability expert. The trouble is, the expert’s writing is not very readable. The first category of problem involves the discrepancy between the characteristics of texts which readability formulas measure and those which we know to influence text comprehensibility. Because most of the formulas include only sentence length and word difficulty as factors, they can account only indirectly for other factors that make a particular text difficult, such as degree of discourse cohesion, number of inferences required, number of items to remember, complexity of ideas, rhetorical structure, dialect, and background knowledge required. Further, because the formulas are measurements based on a text isolated from the context of its use, they cannot reflect such reader-specific factors as motivation, interest, competitiveness, values, and purpose. Here’s my edit:

In addition to shorter sentences, the revision follows several Strunk and White principles: Rule 11 (on paragraphing for white space); Reminder 14, “Avoid Fancy Words”; Reminder 16, “Be Clear”; and the general injunction to give the reader a break. E.B. White says so in his introduction: All through The Elements of Style one finds evidences of the author’s deep sympathy for the reader. Will [Strunk] felt that the reader was in serious trouble most of the time, floundering in a swamp, and that it was the duty of anyone attempting to write English to drain this swamp quickly and get the reader up on dry ground, or at least to throw a rope. In revising the text, I have tried to hold steadily in mind this belief of his, this concern for the bewildered reader. In addition to reviewing Strunk and White, consult Bruce Ross Larson’s Writing for the Information Age, which provides a defense of shorter sentences and bullets as a means of providing white space. For our own elaboration on these principles of readability, please download Write It Right With Strunk and White. |

For answers to specific writing questions,

email us here. Who

knows? Your question may inspire

our next article in Writing

Tips.

Back to top | More Newsletters | Back to Improve Your English

|

WRITING TIP |

Back to top | More Newsletters | Back to Improve Your English |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE

RIGHT WORD |

Leverage Massive Impact!

|

|

| Arthur Moffa, tutor |

by Arthur Moffa

Which is a more massive tax increase: a 5¢ tax on each can of sugary soft drinks sold or an annual $20 tax on everybody? Provided that people paid the 5¢ tax in nickels and the $20 tax in bills, the 5¢ tax would be the more massive, simply because a metal coin has more mass than a paper bill. A tax increase is only massive if it has mass. The tax man no longer carries a set of scales, right?

Mass, like “impact” and “leverage,” has a precise scientific meaning that should limit its use. Of course, there’s no reason to keep these three words locked in the physics laboratory. But we should remain mindful of their origins and not use them in inappropriate contexts just because they sound scientific.

Editors of Merriam-Webster’s dictionary update its entries every ten years to keep up with trends in American English. Here’s the current definition for “massive”:

massive \'ma-siv\ adj 1: forming or consisting of a large mass 2: large in structure, scope, or degree

When people discuss a “massive” tax increase, they are applying Definition 2’s sense of “scope or degree.” A tax increase can certainly be “large in scope or degree.” It might even be big. But should it be massive?

If one really wants to emphasize the scope or degree of a tax increase, one might try expansive, enormous, or major. If one opposes the tax increase, better adjectives might be expensive, ruinous, or even confiscatory. Or perhaps the tax increase is unprecedented or exorbitant. All those words provide more information than massive.

Save massive for descriptions for which the enormous physical size and density of an object really matters: massive asteroids, massive buildings, massive icebergs. Avoid massive when describing an abstract noun: there are no massive sounds, massive ideas, or massive emotions.

Impact is another physics-based word people use in an attempt to sound scientific. Here’s Merriam-Webster:

impact \im-'pakt\ n 1: a forceful contact, collision, or onset 2: the force of impression of one thing on another

vb 1: to press together 2: to have an impact on 3: to strike forcefully

Most people use the noun form correctly: an impact occurs when two things crash together. The verb form, however, is often used incorrectly:

Incorrect: The recent tensions with Iran are sure to impact the price of gasoline.

Incorrect: My opponent’s proposals will impact seniors’ and veterans’ benefits.

Neither sentence describes a collision. Both try to use definition 2: “to have an impact on,” but in each case, impact results in a change. As we note in Write it Right With Strunk and White, the real question, though, is what kind of change? Impact can’t tell us that, and writing is weak when it makes the reader guess unnecessarily. So try these:

Correct: The recent tensions with Iran are sure to increase/raise/inflate the price of gasoline.

Correct: My opponent’s proposals will decrease/lower/diminish seniors’ and veterans’ benefits.

The common words raise and change might seem duller than impact. However, trading clarity for excitement is a fool’s bargain.

The word leverage has been around for a while, but it has grown in popularity (or infamy) since the global financial crisis of 2007-2008. The verb form is particularly tricky. Here’s the actual definition:

leverage \'le-ve-rij, 'lev-rij\ n 1: the action of a lever or the mechanical advantage gained by it 2: power, effectiveness 3: the use of credit to enhance one’s speculative capacity

vb 1: to provide (as a corporation) or supplement (as money) with leverage; also: to enhance as if by supplying with financial leverage

Note that Merriam-Webster’s all but restricts the verb to the context of finance—specifically, when borrowing money to make an investment. In extending the word to other settings, make sure to describe a similar situation: when someone uses something he does not actually have to try to gain something he does not yet have. The following sentences are wrong:

Incorrect: We could leverage Wikipedia for our biography of George Washington.

Incorrect: I will leverage my contacts to find a new job.

The first example is simply bombast; why not use Wikipedia to assist with writing the biography? The second is better, but still wrong. The following version, however, is unambiguously correct, as you can no doubt work out for yourself:

Correct: I will leverage my friends’ contacts to find a new job.

Modern society is impressed with science, which has improved our lives and enriched our language. However, science is a set of disciplines, not a storehouse of rhetorical terms. Thus, don’t leverage massive words to impact certain readers; just use the right words to persuade them. Simple ones, such as big, harm, and use, will serve well.

Back to top | More Newsletters | Back to Improve Your English

|

RECOMMENDED

READING

|

Federalist Number 10 by Nat Crawford In the time that America has existed under a single constitution, Europe has experienced wave upon wave of political reorganization. Since the nineteenth century, Germany has had three constitutions; Spain has had ten; and France—counting only the longer-lasting ones—has had twelve. Even as we speak, Europe’s recent attempt to unite its members in a single “super-state” teeters on the brink of collapse. The history of that continent is a continual struggle of kings with aristocrats, of aristocrats with commoners, of faction with faction. The political story of other nations around the world is substantially the same: different groups struggle to control the ship of state, sometimes achieving a balance, but more often than not throwing it off course. Why did America turn out different? If its people are no more virtuous than those of France or Spain, what has enabled the country to balance the competing interests of bankers and farmers, owners and workers, preachers and politicians for 236 years and counting? It is in large part due to the country’s constitution, whose authors knew full well the dangers of faction. In Federalist Paper Number 10, James Madison explains how the American Constitution limits the damage that factions can cause. This paper is a masterful example of Strunk and White’s Rule 12: “Choose a suitable design and hold to it.” If Madison were with us to explain his technique further, he might make the following points. Begin promptly. In his first sentence, Madison clearly establishes his argument: “Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction.” As Madison originally published this paper in a newspaper, he had to grab his readers with his first words. When writing to please your teacher, you may set your thesis at the end of the intro paragraph; when writing to influence a nation, consider Madison’s approach. Drive home your point. In his first three sentences, Madison misses no opportunity to paint factions as evil. Factions are a “dangerous vice” that entail “violence” and require a “cure” in the form of a sound constitution. Define your terms. By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. Madison separates faction from mere diversity of opinion; by his definition, factions are an inherent threat to the nation as a whole. Organize your argument. Madison subdivides his argument into two main sections: how to prevent the causes of faction and how to prevent its effects. These sections he further subdivides. To remove the causes of faction, one must either “destroy … liberty” or “give … every citizen the same opinions.” To remove the effects of faction, one must examine what to do when the faction composes a minority of the country and what to do when it composes a majority. This last circumstance, which makes up the bulk of Madison’s article, receives further subdivisions, which you should investigate for yourself; together, they form one of the most important arguments ever made for the American system of government. Illustrate your points. Madison enlivens his argument with apt metaphors. For example, he argues against controlling the causes of factions, namely liberty, by comparing liberty to air: though air fuels destructive fires, we need it to breathe. Later, he refutes those who hope for rule by a philosopher-king by using the metaphor of the ship of state: “Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” And with the metaphor of an agricultural crop, he illustrates the permanent desire of humanity to form factions: “The … causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man.” Madison’s argument has itself been sown into our country’s intellectual history. Its final sections on the advantages of representative government are familiar to all Americans from their elementary-school classes on government and citizenship. Yet people easily forget that for all its optimistic discussion of representative government, this argument rests on pessimistic assumptions about human nature. For Madison, people always act in their own interests, their passions inextricably wound into their souls. And even a little power corrupts them. Federalist No. 10 reminds us of how easy it is to misjudge human nature. Calling to mind a few kind or generous actions, we conclude that we ourselves are fundamentally kind and generous. But Madison’s observations suggest that we should reconsider. Have we never joined a destructive mob? Have we never tried to deprive a neighbor of property? Have we never stirred up the chaos that has forced so many other countries to remake their governments? Then perhaps we should thank not natural human virtue, but a constitution that limits our participation in government and that checks our own bad tendencies with those of our equally bad fellow citizens. The people who created the most durable constitution of the modern world had this pessimistic view of humanity before them when they set their quills to paper. Back to top | More Newsletters | Back to Improve Your English |

|

|

info@improveyourenglish.com

Copyright 2003-2013 IYE, Inc. All rights reserved.

This selection scores 100% on the Flesch readability scale. Why? Because it uses short sentences.

This selection scores 100% on the Flesch readability scale. Why? Because it uses short sentences.